Man shares in some ways the life of plants, animals and the angels. He grows like the plants, moves like the animals and used to think as angels before his fall.

Man shares in some ways the life of plants, animals and the angels. He grows like the plants, moves like the animals and used to think as angels before his fall.

Pope Benedict encourages us to go from eros, which is human love according to the nature of man, and climb up to Agape, which obliges us to rise up to the nature of God. Pope Benedict described this as ecstacy.

But ecstacy could work in two ways: man could leave his human nature and rise up to the nature of angels, Pope Benedict’s invitation in his encyclical; or he can leave his human nature and descend to the animal nature which is Satan’s invitation.

This is sensual ecstasy, when man chooses to go below his human nature, to the level of the beasts. It happens when man thinks only of the things of this world and ends up loving the things of this world. His activities are reduced to purely worldly matters, as a lion only looks at his prey or a horse concentrated on the grass. Or, worse, he descends lower, into drug addiction.

Then, there is the human level, where man behaves like a human being: he loves his reason and reason governs his concupiscence to some degree.

Pope Benedict was describing the ecstacy wherein man rises up above his natural capabilities, to a realm outside his human nature, which is possible only through grace. Both the intellect and the will rise up with the help of the Theological virtues. This is the ecstacy that Pope Benedict describes, when both the intellect and the will are raised above and beyond their nature. Scriptures describes this as dying to oneself to live in Christ. It is only by dying to one’s human nature that we can rise up with Christ. Having reached perfect Charity is being in a state of ecstacy. (Sometimes, as in the ecstacies of St. Teresa of Avila, the saint would be unconscious of everything around her to the point of being unable to feel the droppings from a burning candle. St. Thomas often went into such ecstacies. But the common one is more like the ecstacy of St. Catherine of Genoa, who was so conscious of her surroundings that she was once distracted by the passing by of her brother.)

There is an ecstasy of the intellect in the act of admiring the supernatural truth beheld; and there is an ecstasy of the will in the act of loving God. Ordinarily, a saint does not go unconscious or go into a trance. To do so are the more extraordinary instances.

These two ecstasies, that of the will and the intellect, are what Pope Benedict XVI refers to in the first part of his encyclical, which consists in the love of God. But before we can love God (will) we must first know him (intellect) and in these lies the ecstasy of life. Sadly, our knowledge of God is defective, and so our love for God.

In the second part of his encyclical he speaks about love of neighbor. When a soul reaches ecstasy of intellect and will, the consequence is ecstasy of action where the soul gets involved in a fervent service of neighbor. The saint in his contemplation of goodness wants to share his happiness with others. Fervent, because the soul’s activities surpass the abilities of human nature. Good examples of these are St. Vincent the Paul, St. Ignatius of Loyola, and Mother Teresa, among the few mentioned by Pope Benedict at the conclusion of his encyclical. The activities of these saints are ecstacies of action. That’s why their activities cannot be duplicated by ordinary souls.

The sign of a holy life is the presence of the three ecstasies. If one is lacking, we must be cautious; beware of the devil’s tail. A religious may be engaged in feverish activities but if he has not experienced ecstasy in mind and free will, his activity could be suspect. A theologian might show profound theological knowledge but if he does not show love for God and deep concern for neighbor we are facing a fake.

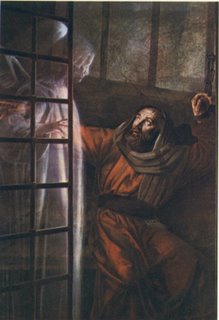

“The Charity of Christ presses us” is a statement of one whose mind and free will are in ecstasy and wherein both presses the soul into ecstacy of action. (Painting of “St. Margaret of Cortona in Ecstasy” by Giovanni Lanfranco, 1622.)